.png)

Guaranteed basic income tackles poverty by targeting cash to those in need. We already have a working examples in seniors and child benefits—this just expands the model to help more people. A broad-based program in Canada would cost 3-5% of total spending and save us money from the even higher costs of poverty (equal to 13% or more of all spending).

In contrast, a universal basic income that goes to everyone is most viable as a dividend from a common fund or resource, like Alaska’s oil dividend to every resident. In Canada, the excess profits from natural resources could generate a dividend of $7,500/year per adult.

Guaranteed basic income and universal dividends can work in tandem to provide economic security for all and allow everyone to share in the value of nature and technological progress.

We can generally distinguish between two dominant models of basic income being explored today, both of which have working examples: 1) a guaranteed basic income (GBI) for those in need as an anti-poverty program; and 2) a universal basic income (UBI) distributed to everyone as a dividend from a common fund or resource.

While there is strong case for universality over means-testing, the prevailing political focus for anti-poverty programs is on directing money to those with the lowest incomes. A universal variant of such a basic income—one that goes to everyone regardless of income and isn't structured as a common dividend—could see the additional income of higher earners taxed back, so that the net result is an income-tested cash transfer.

Under this framework, it becomes evident that many who advocate for UBI actually refer to GBI. This includes governments, politicians, journalists, non-profits, and likely even TV stars. It’s also clear that critics often argue against a different UBI model than what’s on the table politically. This highlights a need for advocates to better coordinate on messaging and public education around viable basic income schemes.

The primary goal of a GBI is poverty reduction. As earned income rises, the benefit amount gradually declines, making it an order of magnitude cheaper than giving everyone equal payments. GBI can be implemented with no new taxes on working Canadians and could save taxpayers money from the even higher costs of poverty in healthcare, crime, and lost productivity.

This model of GBI was tested during the Manitoba Mincome Project in the 1970s. Hospitalization rates decreased 8.5% while median wages increased 6.8%. Most recipients continued working, except new parents and students. Several decades later, it was tested again in the Ontario Basic Income Pilot, where people kept working and became healthier. Over one-third of working pilot recipients surveyed said they found higher paying work.

A national GBI modelled after the Ontario pilot could cost as little as $23B, roughly 3% of all government spending, if it replaced other federal and provincial support programs. If only federal support programs are rolled in, the net cost would be roughly $36B, or 3% of all spending—still lower than the cost of poverty. In comparison, Feed Ontario estimated the annual cost of poverty at approximately $80 billion in 2008, which is equal to more than 13% of all government spending that year ($607B according to StatCan). The cost of poverty is likely much higher today.

In Prince Edward Island, a basic income capable of reducing poverty by 80% would cost merely 1% of the province’s GDP. The Parliamentary Budget Officer estimated that basic income would have a “very low” impact on work — about 0.6% or “a few hours a year”. UBC economist Dr. David Green concluded that inflation “wouldn’t be a major concern”. The Canadian Centre for Economic Analysis estimated that a GBI could grow Canada’s economy by more than it costs and create hundreds of thousands of jobs, while ending poverty.

This idea comes in many names and variants—negative income tax (NIT), guaranteed livable income (GLI), guaranteed livable basic income (GLBI), guaranteed annual income (GAI), guaranteed minimum income (GMI), basic income guarantee (BIG), unconditional basic income—but the core idea remains consistent: give cash directly to people in need.

We already have effective versions of this today in our child and seniors benefits, which have been overwhelmingly successful in lowering poverty rates in Canada. Here are notable examples basic income-like programs:

A broader guaranteed basic income simply expands on these to programs to help more people in need.

UBI is about sharing wealth from a common fund or resource, like Alaska’s oil dividend to all residents or Sam Altman’s proposal for an AI Dividend fund. Whereas GBI targets poverty, UBI dividends give citizens a stake in something we have a shared claim to, such as wealth generated by nature, public infrastructure, or technological progress. Paying common dividends is a fair and efficient way to tackle extreme inequality, safeguard common resources, and better distribute returns to capital in an automating economy.

With UBI dividends, the funding source is baked in, unlike GBI which can be funded through various means to achieve its poverty reduction goal. Leading UBI advocates generally agree that it should be financed by sources of common wealth, rather than taxing workers. The Former Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis believes that “If a universal basic income – liberty's main prerequisite in an age of obsolete labor – is to be legitimate, it cannot be financed by taxing Jill to pay Jack.”

Common Wealth Canada estimated that the economic rent (i.e. unearned or excess profits) arising from Canada’s land and natural resources could generate roughly $7,500/year in dividends per adult. They also published a framework for a Canadian sovereign wealth fund that could pay dividends from investing the nation’s natural resources and other publicly created wealth.

Rahul Basu of the Goa Foundation showed from StatCan data that Canada is on track to lose 77% of its mineral wealth to private extraction. That's equivalent to nearly $1 trillion that could be invested in a sovereign wealth fund, generating a real dividend of $940/year per Canadian in perpetuity.

Ironically, some critics of basic income are strong advocates of the UBI dividend model. Conservative-leaning organizations Fraser Institute and Canadian Taxpayers Federation have both championed Alaska-style resource dividends for Canada. The Fraser Institute estimated that the Alberta Heritage Fund—established to invest the province’s non-renewable resource revenues—could distribute $4,400/year in dividends per family if managed like the Alaska Permanent Fund. They’ve also advocated for Newfoundland & Labrador’s Future Fund to adopt Alaska’s dividend-paying model. Similarly, the CTF proposed a Saskatchewan Heritage Fund that could pay UBI dividends from investing the province’s resource revenues.

Here are other notable proposals for universal dividends:

In the era of advancing AI and job automation, GBI and UBI are crucial to preserving equality of opportunity and maintaining a strong middle class. Technology is steadily erodings workers’ share of income, as rising productivity funnels a larger share of wealth into land and other assets. The result is an economy where owning assets increasingly generates more wealth than working—a world where having trumps doing.

.png)

.png)

.png)

Automation has created a polarizing job market where middle-skill jobs are replaced by more low- and some high-skill jobs. Meanwhile, the earnings gap between education levels is widening. Labour-enhancing technologies augment incomes for workers with complementary skills, while others see their income potential competed away.

.png)

.png)

.png)

During previous industrial revolutions, workers eventually reaped the full benefits of rising productivity. However, inequality grew for generations and real wages stagnated for an uncomfortably long time. The 4th industrial revolution of human-level AI and robotics may produce a similar outcome, but on a larger scale.

In the words of Dr. Karl Widerquist: “Even if the total number of jobs increases with automation, innovation disrupts the labour market… Their children or grandchildren might eventually get better jobs, but this is cold comfort to people spending the rest of their lives at the bottom of the labour market.”

GBI provides an economic floor noone can full under. For workers affected by automation, it buys time to retrain and to weather periods of precarity. It gives people the economic power to say no to poverty wages and poor working conditions. It gives people freedom to take important risks like starting a business, going back to school, changing careers, or escaping a bad situation.

UBI gives everyone a financial stake in the value generated by nature and technological progress. It tackles extreme inequality at its root by ensuring that the value of nature benefits everyone, not just those who claimed the resources first. It provides everyone with a dividend income that directly ties their financial well-being to the success of the broader economy. As automation continues to widen the gap between returns to capital and returns to wage labour, UBI gives everyone a source of income divorced from work.

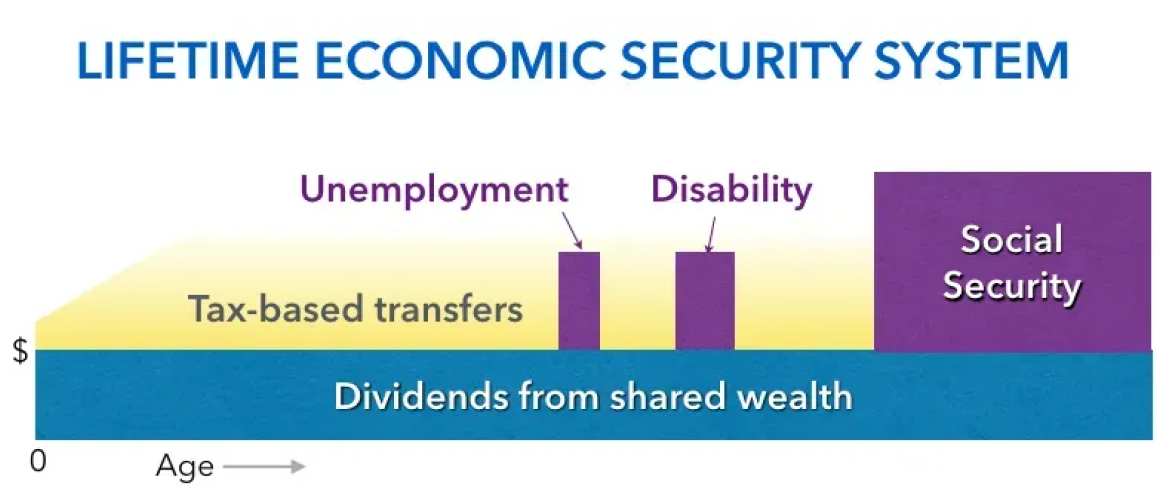

As the following visual demonstrates, universal dividends (blue) can work in tandem with targeted basic incomes (yellow and purple) to provide lifetime economic security for all.

Opponents often conjure up economically unfeasible UBI schemes with astronomical costs only to discredit them without opposition. Here are a few examples:

These imaginations of UBI bear little resemblance to what advocates or policymakers working on basic income are actually for. They reflect a broader phenomenon of people who debate with a fictional idea of basic income rather than engaging with reality.

One of the most common errors critics make is conflating the Canada Emergency Response Benefit with UBI—a prime example of what basic income is not. CERB was a temporary program that initially included a crippling work disincentive no reasonable basic income design would ever have: a punitive 100% clawback of the benefits when recipients went back to work.

Even the Conservatives proposed making it more like a guaranteed basic income by introducing a gradual clawback to encourage work. They called it the “Back To Work Bonus”. The Liberals would later incorporate this work-incentivizing design into CERB’s successor, the Canada Response Benefit, but not before mass confusion led many to mistaken CERB as the definitive model of UBI.

Because critiques often fail to understand the distinction between guaranteed basic income and universal dividends, they are at best misinformed and at worst disingenuous strawman arguments. No policymaker or advocate would seriously discuss raising taxes on working families to fund monthly cheques to all. Critics are often debating a fictional idea that has no chance of implementation and fulfills neither the purpose of a GBI nor a UBI dividend.

Guaranteed basic income tackles poverty, saving lives and money. UBI shares wealth we all have a claim to. We already have working models of each—let’s build on those.

By Ken Yang